Educational Technology

Models of teaching and learning

In the context of educational technology two questions are to be answered.

- “Why do some students learn required knowledge and skills taught in school, while others do not?”- a criterion-referenced evaluation question

- “Why do some students learn more than other students?”- a norm-referenced evaluation question.

Unfortunately, the possible answers to these questions are enormous. Oftentimes research findings and theories of teaching and learning seem to contradict one another.

With this background McIlrath and Huitt, (1998) explored several models of teaching and learning and made conclusions which are presented below.

Gage & Berliner (1992) stated that the use of models as learning aides have two primary benefits. First, models provide accurate and useful representations of knowledge that is needed when solving problems in some particular domain. Second, a model makes the process of understanding a domain of knowledge easier because it is a visual expression of the topic. They found that students who study models before a lecture may recall as much as 57% more on questions concerning conceptual information than students who receive instruction without the advantage of seeing and discussing models.

Alesandrini (1981) came to similar conclusions when he studied different pictorial-verbal strategies for learning, as described below.

John Carroll’s Model

Most current models that categorize the variables or explanations of the many influences on educational processes today stem from Carroll’s (1963) seminal article defining the major variables related to school learning. Carroll specialized in language and learning, relating words and their meanings to the cognitive concepts and constructs which they create (Klausmeier & Goodwin, 1971). In his model, Carroll states that time is the most important variable to school learning. A simple equation for Carroll’s model is:

School Learning = f (time spent/time needed).

Carroll explains that time spent is the result of opportunity and perseverance. Opportunity in Carroll’s model is determined by the classroom teacher; the specific measure is called allotted or allocated time (i.e., time allocated for learning by classroom teachers.) Perseverance is the student’s involvement with academic content during that allocated time. Carroll proposed that perseverance be measured as the percentage of the allocated time that students are actually involved in the learning process and was labeled engagement rate. Allocated time multiplied by engagement rate produced the variable Carroll proposed as a measure of time spent, which came to be called engaged time or time-on-task.

Carroll (1963) proposed that the time needed by students to learn academic content is contingent upon aptitude (the most often used measure is IQ), ability to understand the instruction presented (the extent to which they possessed prerequisite knowledge), and the quality of instruction students receive in the process of learning. Carroll proposed that these specific teacher and student behaviors and student characteristics where the only variables needed to predict school learning; he did not include the influences of family, community, society and the world that other authors discussed below have included.

The principles of this model can be seen in Bloom’s (1976) Mastery Learning model. Bloom, a colleague of Carroll’s, observed that in traditional schooling a student’s aptitude for learning academic material (IQ) is one of the best predictor’s of school achievement. His research demonstrated that if time is not held constant for all learners (as it is in traditional schooling) then a student’s mastery of the prerequisite skills, rather than aptitude, is a better predictor of school learning. Mastery Learning’s basic principle is that almost all students can earn A’s if

- students are given enough time to learn normal information taught in school, and

- students are provided quality instruction.

By quality instruction Bloom meant that teachers should:

- organize subject matter into manageable learning units,

- develop specific learning objectives for each unit,

- develop appropriate formative and summative assessment measures, and

- plan and implement group teaching strategies, with sufficient time allocations, practice opportunities, and corrective reinstruction for all students to reach the desired level of mastery.

Proctor’s Model

Proctor (1984) provides a model that updates this view by including important teacher and student behaviors as predictors of student achievement. It is derived from other teacher- and classroom-based models but is redesigned to emphasize teacher expectations. Proctor states that it is possible for a self-fulfilling prophesy (as researched by Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968) to be an institutional phenomenon and the climate of a school can have an effect on the achievement of its learners. The attitudes, the norms, and the values of an educational faculty and staff can make a difference in achievement test scores. The paradigm most influencing Proctor’s model is that of a social nature and not of a teacher/student one-on-one relationship. The other models include the variables that provide the focus for this model, but show these variables in a more subordinate manner.

Proctor’s model begins with the factor of the School’s Social Climate. Some of the variables included in this would be attitudes, norms, beliefs, and prejudices. This school climate is influenced by a number of factors, including such student characteristics as race, gender, economic level, and past academic performance. The student characteristics also influence teacher attitudes and teacher efficacy.

The next category of variables is the interaction among the individuals involved in the schooling process. This includes the input of administrators as well as that of teachers and students. If expectations of learning are high (i.e., the school has good, qualified teachers and students who can learn) and there is high quality instructional input, corrective feedback, and good communication among students, parents, and educators, then the intermediate outcomes of student learning and student self-expectation goes up. On the other hand, adverse or negative attitudes on the part of instructors and administrators will cause student self-esteem, and consequently, student achievement to spiral downwards.

The interactions in Proctor’s (1984) model include the school’s overall policy on allowing time for children to learn or promoting other forms of student-based help when needed. This could include quality of instruction (as in Carroll’s (1963) model above) or teacher classroom behaviors (as in Cruickshank’s (1985) model below). These behaviors have an effect on student classroom performance (especially academic learning time and curriculum coverage) and self-expectations .

Finally, the student’s achievement level in Proctor’s (1984) model is an outcome of all previous factors and variables. It is hypothesized that there is a cyclical relationship among the variables. In Proctor’s model, the main concept is that achievement in a specific classroom during a particular school year is not an end in itself. It is refiltered into the social climate of the school image and the entire process begins all over again. Proctor’s model implies that change can be made at any point along the way. These changes will affect school achievement, which will continue to affect the social climate of the school.

Cruickshank’s Model

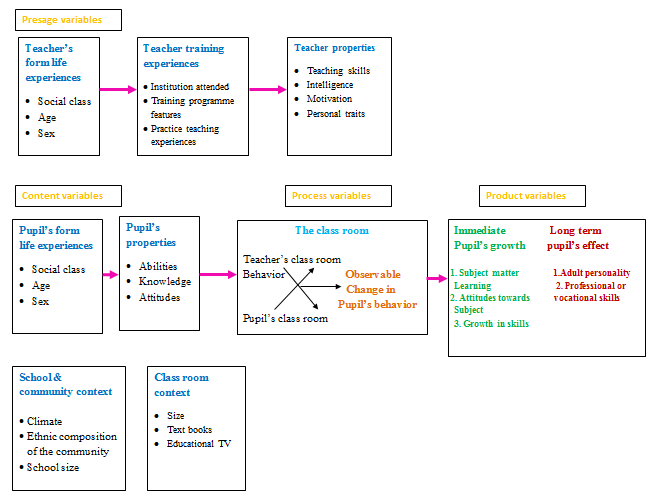

The model by Cruickshank (1985) is more classroom- and teacher-based. Product is learning on the part of the student (change in behavior or behavior potential) while process involves interaction between student and teacher. Presage is the teacher’s intelligence, level of experience, success and other teacher characteristics. Presage is supposed to affect process and then, of course, process will affect the product. **** image

Biddle Model

Biddle (as cited in Biddle & Ellena, 1964) showed a relationship between specific learning activities and teacher effects. In his model, Biddle offers seven categories of variables related to schooling and student achievement: school and community contents, formative experiences, classroom situations, teacher properties, teacher behaviors, intermediate effects, and long-term consequences. This provides the foundation for Cruickshank’s (1985) model.

Biddle also contributed a model of the transactional process of the classroom by analyzing the structure and function of the communication process. This is reflected in Cruickshank’s model through the use of arrows depicting the interaction between teacher and pupil classroom behavior.

Biddle constructed his models to help answer questions he thought parents might ask, such as: “How often does my child get individual attention from the teacher?” Or, “Does the teacher really understand Junior’s special problem?” (Adams & Biddle, 1970, p. 6). Biddle also helped define non-cognitive variables which contribute to the affective domain (i.e., self-concept and self-esteem of the students). An example of these variables would be teacher genuineness, “teacher-offered conditions of respect…and modification of low self-concept” (Good, Biddle & Brophy, 1975, p. 195).

Flanders (as cited in Cruickshank, 1985) offered the variables of teacher- and student-classroom-talk and devised an instrument which focused on this behavior. “His was the most frequently used instrument. It permitted observation of teachers’ use of ‘verbal influence,’ defined as ‘teacher talk’ and ‘pupil talk,’ in a variety of classroom situations” (Cruickshank, p. 17). Cruickshank put them all together and added additional presage variables such as pupil characteristics, properties (abilities and attitudes) and school, community and classroom climate.

Gage and Berliner’s Model

Gage and Berliner (1992) developed a model of the instructional process that focuses on those variables that must be considered by the classroom teacher as she designs and delivers instruction to students. This model attempts to define more precisely what is meant by “quality instruction” and presents five tasks associated with the instruction/learning process. The model is classroom- and teacher-based and centers around the question, “What does a teacher do?”

A teacher begins with objectives and ends with an evaluation. Instruction connects objectives and evaluations and is based on the teacher’s knowledge of the students’ characteristics and how best to motivate them. If the evaluations do not demonstrate that the desired results have been achieved, the teacher re-teaches the material and starts the process all over again. Classroom management is subsumed under the rubric of motivating students. Gage and Berliner suggest that the teacher should use research and principles from educational psychology to develop proper teaching procedures to obtain optimal results.

Huitt’s model

Huitt’s model attempts to categorize and organize all the variables that might be used to answer the question, “Why do some students learn more than other students?” This is a revision of a model by Squires, Huitt and Segars (1983) which focused only on those variables thought to be under the control of educators. This earlier model focused on school- and classroom-level processes that predicted school learning as measured on standardized tests of basic skills. One important addition in this model is the redefinition of Academic Learning Time. It had long been recognized that Carroll’s conceptualization of time spent measured the quantity of time engaged in academics, but was lacking in terms of the quality of that time. As discussed in Proctor’s (1984) model, Fisher and his colleagues (1978) had added the concept of success as an important component of quality of time spent and coined the term Academic Learning Time (ALT) which they defined as “engaged in academic learning at a high success rate.” Brady, Clinton, Sweeney, Peterson, & Poynor (1977) added another quality component–the extent to which content covered in the classroom overlaps to content tested–which they called content overlap. Squires et al. used the more inclusive definition of ALT proposed by Caldwell, Huitt & Graeber (1982)–“the amount of time students are successfully engaged on content that will be tested.”

Huitt advocates that important context variables must be considered because our society is rapidly changing from an agricultural/industrial base to an information base. From this perspective, children are members of a multi-faceted society, which influences and modifies the way they process learning as well as defines the important knowledge and skills that must be acquired to be successful in that society. Huitt’s model shows a relationship among the categories of Context (family, home, school, and community environments), Input (what students and teachers bring to the classroom process), Classroom Processes (what is going on in the classroom),and Output (measures of learning done outside of the classroom). These categories appear superimposed in the model since it is proposed they are essentially intertwined in the learning process.

Interpretations

Huitt supports Proctor’s (1984) position that intermediate outcomes, or more specifically Academic Learning Time (ALT) is one of the best Classroom Process predictors of student achievement. As stated above ALT is defined as “the amount of time students are successfully involved in the learning of content that will be tested.” There are three components to ALT and each is as important as the other. The first is Content Overlap, defined as “the extent to which the content objectives covered on the standardized test overlaps with the content objectives covered in the classroom.” This variable has also been labeled as “time-on-target.” The idea is simple: if an objective or topic is not taught, it is not likely to be learned, and therefore we cannot expect students to do well on measures of that content. In fact, to the extent the content is not specifically taught, the test becomes an intelligence test rather than an achievement test. The fact that many educators do not connect instructional objectives to specific objectives that will be tested (Brady et al., 1977), is one reason that academic aptitude or IQ is such a good predictor of scores on standardized tests. Both tests measure the same construct: the amount of general knowledge an individual has obtained that is not necessarily taught in a structured learning setting.

The second component of ALT is Student Involvement, defined the same way that Carroll defined engaged time or time-on-task (allocated time X engagement rate). If the students are not provided enough time to learn material or are not actively involved while teachers are teaching they are not as likely to do well on measures of school achievement at the end of the year.

The last element is that of Success, defined as “the percentage of classwork that students complete with a high degree of accuracy.” If a student is not successful throughout the year on classroom academic tasks, that student will likely not demonstrate success on the achievement measure at the end of the year.

Huitt proposes that these three components of Academic Learning Time should be considered as the “vital signs” of a classroom. Just as a physician looks at data regarding temperature, weight, and blood pressure before asking any further questions or gathering any other data, supervisors need to look at the content overlap, involvement, and success before collecting any other data or making suggestions about classroom modifications. Classrooms where students are involved and making adequate progress on important content are reasonably healthy and quite different from those classrooms where students are not.

In addition to the teacher’s classroom behavior, other time components such as the number of days available for going to school (the school year), the number of days the student actually attends school (attendance year), and the number of hours the student has available to go to school each day (school day) can influence ALT (Caldwell et al., 1982). None of these additional time variables were included in Carroll’s (1963) model.

Each of the above models identifies important factors related to school learning and contributes important information as we attempt to answer the question “Why do some students learn more than others?” Over a period of years, the models have been examined, reviewed, revised and edited to fit into today’s modern society. Beginning with Carroll (1963) and ending (at least as far as this review is concerned) with Huitt (1995), we see teachers and school systems, families, communities and entire countries having an influence on students’ school learning. None of the variables appears to be so influential that we need only pay attention to that particular factor in order to produce the kinds of educational changes we desire. For example, an individual teacher could project his self-fulfilling prophesies on a student (as seen in Cruickshank’s 1985 model), but so also could the institution itself (as seen in Proctor’s 1984 model). Or the school may be successful in developing students’ basic skills, but students could still not be successful in life because other important outcomes were not developed (Whetzel, 1992).

Understanding all the variables and the relationships among each other and to student success may be more than we can expect of any educator. We may never fully grasp the significance of the entire process, but we can make every effort to understand as much as possible as we develop the teaching/learning processes appropriate for the information age. We can also identify the most important variables within a category or subcategory and make certain we attend to a wide variety of variables across the model.

Models are useful tools to better understand not only the learning processes of students, but ourselves as educators. At a glance the models might provide only more questions, but a careful study of the models can provide starting points to begin developing more appropriate educational experiences for our society’s next generation.

Referecnces

McIlrath, D., & Huitt, W. (1995, December). The teaching-learning process: A discussion of models. Educational Psychology Interactive.

Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved [date], from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/modeltch.html